Twelve years ago, in an interview, the renowned Palestinian actor Saleh Bakri was asked whether we would see him in new Palestinian films. He replied:

“I want to be part of Palestinian cinema. I want to create something that belongs to me, something that belongs to us. But at the moment, there’s no project on the horizon. Still, I’m sure it will come. The youth are incredibly active, and I’m very hopeful about the younger Palestinian generation.”

Twelve years later, today, watching Saleh Bakri appear in not one but two powerful films on the big screen fills us with excitement and moves us to tears as we witness the remarkable progress Palestinian cinema has made.

“All That’s Left of You” is only one of these outstanding works.

The film centers on the collective and individual traumas experienced by the Palestinian people and shows how these wounds are passed down across three generations. Communities often place a past catastrophe at the heart of their collective identity, and this traumatic memory is transmitted over generations. Trauma thus becomes a foundational element of both family identity and social identity. Those who did not live through the original event internalize the memories of their parents as if they were their own. This new generation inherits the past at once distant from it, yet deeply permeated by it.

In other words, the individual inner world and the memory of an entire society intertwine; each becomes the silent witness of the other.

Social trauma signifies a rupture far deeper and broader than an individual wound. War, forced displacement, massacres, loss, exile, repression, and erased histories not only affect those who directly experienced them, but also shape the emotional and psychological world of their children and grandchildren. In psychology, this is called transgenerational trauma.

“All That’s Left of You” portrays exactly this phenomenon, weaving it through the lives of three generations of a single family.

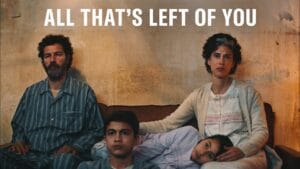

The story begins when Noor (Muhammad Abed Elrahman), a young Palestinian boy, is injured during a protest in the West Bank. His mother, Hanan (Cherien Dabis), decides to recount the chain of events that led to this moment by taking us back through her family’s history. In a powerful, fragile, yet determined tone, we see Hanan in a close-up shot speaking directly into the camera. We hear her words though we will only understand to whom she is speaking at the very end of the film:

“You don’t know very much about us. It’s OK, I’m not here to blame you, I’m here to tell you who is my son. But for you to understand, I must tell you what happened to his grandfather.”

Her voice carries us back to 1948, the Nakba. We arrive in Jaffa, in the youth of Noor’s grandfather, where he and his family live a peaceful, almost magical life surrounded by orange groves.

This is only the first of the film’s four distinct temporal chapters representing the first of the three generations. As Sharif (Adam Bakri), the grandfather, struggles to protect his orange grove in Jaffa, he is confronted with displacement and imprisonment. His refusal to abandon his land illustrates just how profound one’s connection to a place can beemotionally, existentially, and in terms of identity.

Forced to leave their home, Sharif and his family become refugees. We then move to 1978, the period representing the second generation. Sharif’s son, Salim (Saleh Bakri), has grown up; his mother has passed away; and he now lives in a cramped home with his father, wife, and children.

One of the most striking scenes of the film takes place within this timeline. Before Noor’s eyes, Salim is humiliated by Israeli soldiers and Noor’s respect and trust for his father are shattered in an instant. The scene also symbolizes the passing of the torch from the second generation to the third a transfer of resistance, anger, and longing. While Salim carries the unresolved trauma of displacement and suppression, Noor is drawn into protest under the shadow of both his father and grandfather. Structurally, the film interlaces their personal stories into an intimate family epic that bridges political history with private history.

After Noor is shot, the narrative shifts into a different emotional dimension, deepening the weight of this inherited psychological burden.

Watching three generations of the Bakri family on screen is a pleasure in itself. Mohammed Bakri, known for Jenin Jenin, one of the most significant works of Palestinian cinema appears alongside his sons and grandson, creating a truly exceptional cinematic experience.

Covering the periods of 1948, 1978, 1988, and the early 2000s, the film does not present a passive narrative of victimhood; rather, it focuses on dignity, resistance, and confronting one’s own history.

Although certain scenes lean slightly toward an explanatory, almost educational tone, the narrative flow remains compelling and immersive. Toward the end, the pacing feels a bit rushed, and some major decisions lack deeper contextual grounding leaving the audience with a sense that something is missing. As someone who enjoys Palestinian cinema, I admit these flaws did not bother me greatly. There were a few moments when I found myself asking, “Could this have been developed more?” But considering the film’s length, I can understand why the director might have had to omit certain elements.

In just 12 years, the progress Palestinian cinema has made is powerful enough to shake even those who continue to turn a blind eye to the genocide in Gaza. There’s one crucial point that Palestinian filmmakers and international filmmakers who stand with Palestine, never fail to emphasize: “We draw our strength from the people of Gaza.”

Throughout history, cinema has been one of the most effective tools for revealing what is unseen, amplifying voices that must be heard, and leaving a visual record for future generations. And in recent years, we have proudly witnessed how this medium has become a vital instrument of resistance for the Palestinian people.

Films like The Voice of Hind Rajab, Palestine 36, No Other Land, 200 Meters, The Present, Farha, Bye Bye Tiberias, The Teacher, and Once Upon a Time in Gaza are among the strongest examples of how far Palestinian cinema has come. And for those of us who support Palestinian cinema, there is simply no greater joy than experiencing these powerful films on the big screen.